Looking at the plain, one-story wooden shacks that dot the countryside in Cuba’s vuelta abajo region, one would never guess that the farmers here grow one of the island’s most valuable natural resources: cigar tobacco.

Though Cuban cigars are famous worldwide, the majority of the tobacco that goes into premium cigars is grown in this relatively small valley in Western Cuba that possesses a unique micro-climate and rich volcanic soil.

The fields behind Hirochi Robaina’s house are full of mature tobacco plants, and the drying houses where the tobacco hangs and ages for at least 30 days are stacked to the rafters. But the fifth-generation tobacco grower is still not happy with this year’s harvest.

“This year was very complicated because of the weather,” he said. “The weather was bad. A lot of rain and wind.”

Usually, the winter months are the dry season, perfect for growing and harvesting tobacco for top brands like Cohiba, Montecristo and Partagas.

With this harvest, though, there was so much rain that fields are muddy. Some of the plants are flopping over or have grown so tall that they need to be pruned so the leaves, which are rolled into cigars, don’t lose their potency.

“It’s not normal. We start to grow tobacco in November. Normally, there’s no rain, just a little bit,” Robaina said. “But it changed a lot, very strong rain, very strong wind. It’s a big problem for tobacco farmers.”

The problem, he said, is the increased impact of climate change being felt on the Caribbean island.

In January, a freak weather system struck the western part of Cuba, causing a tornado that flipped cars, tore roofs off buildings and killed at least six people in Havana. Cuban weather forecasters said that in 500 years of recorded history, there has never been another tornado to hit the Cuban capital.

On Robaina’s farm, a two-hour drive from Havana, he pointed out the bare patches in his fields where winds from the same storm ripped out whole plants.

“We never had anything like this happen before here,” said Robaina, the youngest member of one of Cuba’s most storied tobacco-growing families. His grandfather Alejandro Robaina was a legend among Cuban cigar aficionados, and the tobacco he produced was saved for Fidel Castro’s personal supply of cigars.

To deal with the unpredictable weather, Robaina said, he’s consulting the detailed notes his grandfather left him on how to grow top-quality tobacco.

Many of his neighbors, he said, are switching from tobacco to crops such as corn and black beans that are easier to grow. That’s like a winemaker in Napa Valley or Bourdeaux deciding to stop growing grapes.

For Robaina, growing anything but cigar tobacco in the place that has the best climate and soil is not an option.

“Robainas have to grow tobacco,” he said. “We have to. This our life.”

The impacts of climate change don’t appear to have affected the bottom line for Cuba’s cigar industry.

At Cuba’s yearly cigar festival in February, the Habanos company, a foreign joint venture with the Cuban government that sells Cuban cigars abroad, announced record sales of $537 million in 2018.

But cigar experts said climate change could affect quality, as well as production.

“It’s something to be concerned about,” said David Savona, executive editor of Cigar Aficionado magazine. “When you are a cigar lover, you are smoking just tobacco. Cigars like these are made only with tobacco and time. If there is a problem with the weather, it’s going to have a direct effect on the cigar.”

Habanos executives said the Cuban government recognizes the impact that climate change could have on an island already vulnerable to hurricanes and coastal flooding and is responding to the potential fallout.

“We are working to mitigate the damage caused by climate change,” said Ernesto Gonzalez, Habanos’ operational marketing director. “Cuba is an example for the world on how to prevent natural disasters.”

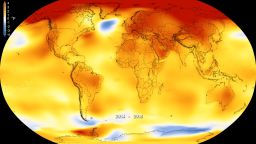

Under a plan called Tarea Vida, or “assignment life,” the Cuban government is studying where the island will most be affected by climate change. According to government data, in the past 70 years, the average annual temperature has risen 0.9 degrees Celsius. Rising sea levels have affected about 85% of the island’s coastline, and the government has banned new construction in some coastal areas and begun to move at-risk communities farther inland.

The Cuban government said in November that tobacco growers had designed new drying houses to cure tobacco with metal roofs, instead of wood, that were more resistant to increased wind and rainfall caused by climate change.

Robaina said he’s concerned that as climate change makes it harder to grow tobacco, Cuban cigar production will go the way of coffee and sugar production on the island and cease to be a major export.

“We have to fight now,” he said. “To save our tobacco.”

![November 9, 2018 - Malibu, California - A row of palm trees stands towers as the Woolsey Fire continues to burn in Malibu, California. (Credit Image: © Joel Angel Juarez/ZUMA Wire) (Newscom TagID: zumaamericastwentytwo367146.jpg) [Photo via Newscom]](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/181111084309-60-california-wildfires-1111.jpg?q=x_0,y_127,h_1371,w_2437,c_crop/h_144,w_256)